Solving long-sought protein structure opens new avenues for treating disease

Scientists at Sanford Burnham Prebys have identified the long-sought structure of an essential blood protein: vitronectin. Knowing the protein’s structure—an advance that enables rational drug design—could lead to medicines that kill multi-drug-resistant bacteria, halt cancer metastasis, treat age-related macular degeneration (AMD) and more. The study was published in Science Advances.

“For decades, scientists have speculated about the shape of vitronectin, but no one had a true answer,” says Francesca Marassi, Ph.D., senior author of the study and professor at Sanford Burnham Prebys’ NCI-designated Cancer Center. “Our findings provide a blueprint for understanding and targeting this important human protein.”

Since vitronectin’s discovery in the 1960s, scientists recognized that the protein is an important drug target and sought to decipher its complex structure. The protein regulates many fundamental processes, including blood clotting, immunity, tissue development and cell attachment. When these functions are disrupted, disease can arise: Deadly tumor metastasis occurs when cancer cells gain the ability to spread through the body, and pathogens such as Y. pestis (plague), H. influenzae (pneumonia, meningitis), N. gonorrhoeae (gonorrhea) and H. pylori (stomach ulcers), hijack vitronectin to evade detection by our immune system. However, without a 3D structure, understanding of the protein’s precise function in the body and the ability to design medicines that block or enhance this function were limited.

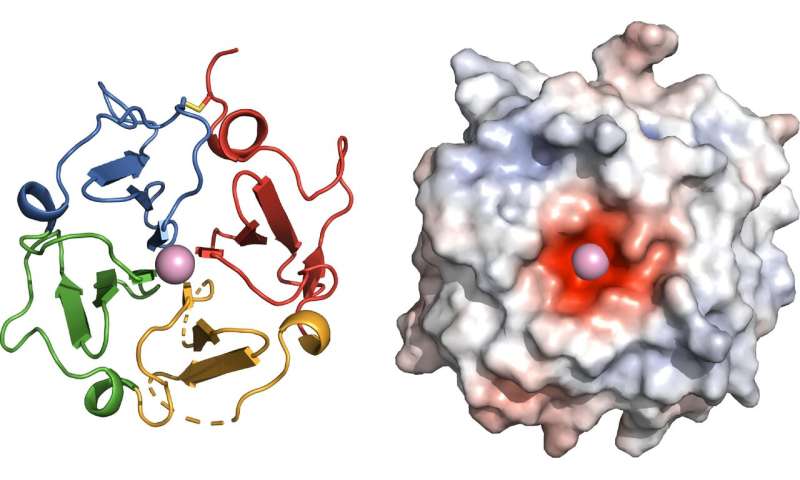

To visualize the protein’s structure, Marassi and her team analyzed evolutionary clues and then turned to X-rays and magnetic resonance, an MRI-like technology. The researchers found that the functional site of vitronectin forms a four-bladed propeller with a negatively charged center that binds calcium. This work revealed the binding site of the protein Ail, which Y. pestis bacteria use to hijack vitronectin and evade the immune system—an important insight for antibiotic drug development in the event plague becomes antibiotic resistant or is ever weaponized.

“Now we see why vitronectin has so many ‘jobs’ in the body,” explains Marassi. “The propeller acts as a hub for multiple biological activities. The protein’s overall shape and its negatively charged center provide additional insights about its cholesterol and calcium binding properties.”

“The many faces of vitronectin continue to amaze,” says Erkki Ruoslahti, M.D., Ph.D., distinguished professor at Sanford Burnham Prebys, who discovered the protein’s adhesive properties and named it ‘vitronectin’ based on its ability to stick to glass surfaces. “The first function assigned to vitronectin was that cells in our blood and tissues attach to it, but it has since turned out to have many other functions. The vitronectin structure that the Marassi team reports is an important milestone. They show that the bacteria that cause plague bind vitronectin at a site different from that previously known for cell attachment, suggesting that bacteria use vitronectin as a bridge to bind human host cells and enhance their infective powers.”

Having the structure of vitronectin in hand is already revealing new insights into human disease. With this information, Marassi made the connection that the shape of vitronectin correlates with its known involvement in AMD, a condition marked by progressive loss of sight.

Source: Read Full Article