The viruses in our genes: When activated, they impair brain development

Since our ancestors infected themselves with retroviruses millions of years ago, we have carried elements of these viruses in our genes—known as human endogenous retroviruses, or HERVs for short. These viral elements have lost their ability to replicate and infect during evolution, but are an integral part of our genetic makeup. In fact, humans possess five times more HERVs in non-coding parts than coding genes. So far, strong focus has been devoted to the correlation of HERVs and the onset or progression of diseases. This is why HERV expression has been studied in samples of pathological origin. Although important, these studies do not provide conclusions about whether HERVs are the cause or the consequence of such disease.

Today, new technologies enable scientists to receive a deeper insight into the mechanisms of HERVs and their function. Together with her colleagues, virologist Michelle Vincendeau has now succeeded for the first time in demonstrating the negative effects of HERV activation on human brain development.

HERV activation impairs brain development

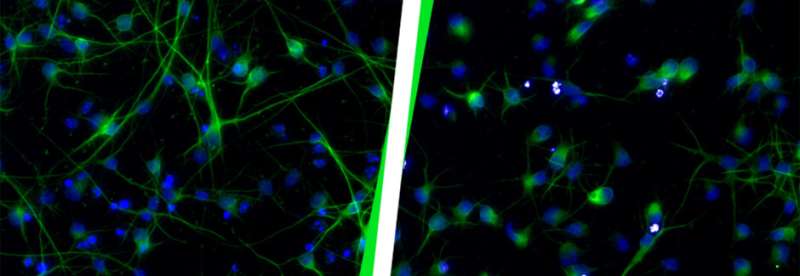

Using CRISPR technology, the researchers activated a specific group of human endogenous retroviruses in human embryonic stem cells and generated nerve cells (neurons). These viral elements in turn activated specific genes, including classical developmental factors, involved in brain development. As a result, cortical neurons, meaning the nerve cells in our cerebral cortex, lost their function entirely. They developed very differently from healthy neurons in this brain region—with much a shorter axon (nerve cell extension) that was much less branched. Thus, activation of one specific HERV group impairs cortical neuron development and ultimately brain development.

Clinical relevance

Since neurodegenerative diseases are often associated with the activation of several HERV groups, the negative impact of HERV activation on cortical neuron development is an essential finding. It is already known that environmental factors such as viruses, bacteria, and UV light can activate distinct HERVs, thereby potentially contributing to disease onset. This knowledge, in turn, makes HERVs even more interesting for clinical application. Switching off distinct viral elements could open up a new field of research for the treatment of patients with neurodegenerative diseases. In a next step, the group at Helmholtz Zentrum München will study the impact of HERV deactivation in neurons in the context of disease.

New paths for basic research

Source: Read Full Article