UK hospital study explores whether monkeypox can be transmitted through aerosolized droplets and fomites

In a recent study published in The Lancet Microbe, researchers conducted an observational study to determine environmental contamination with the monkeypox virus in hospital isolation rooms of monkeypox patients to understand potential exposures to healthcare workers.

Background

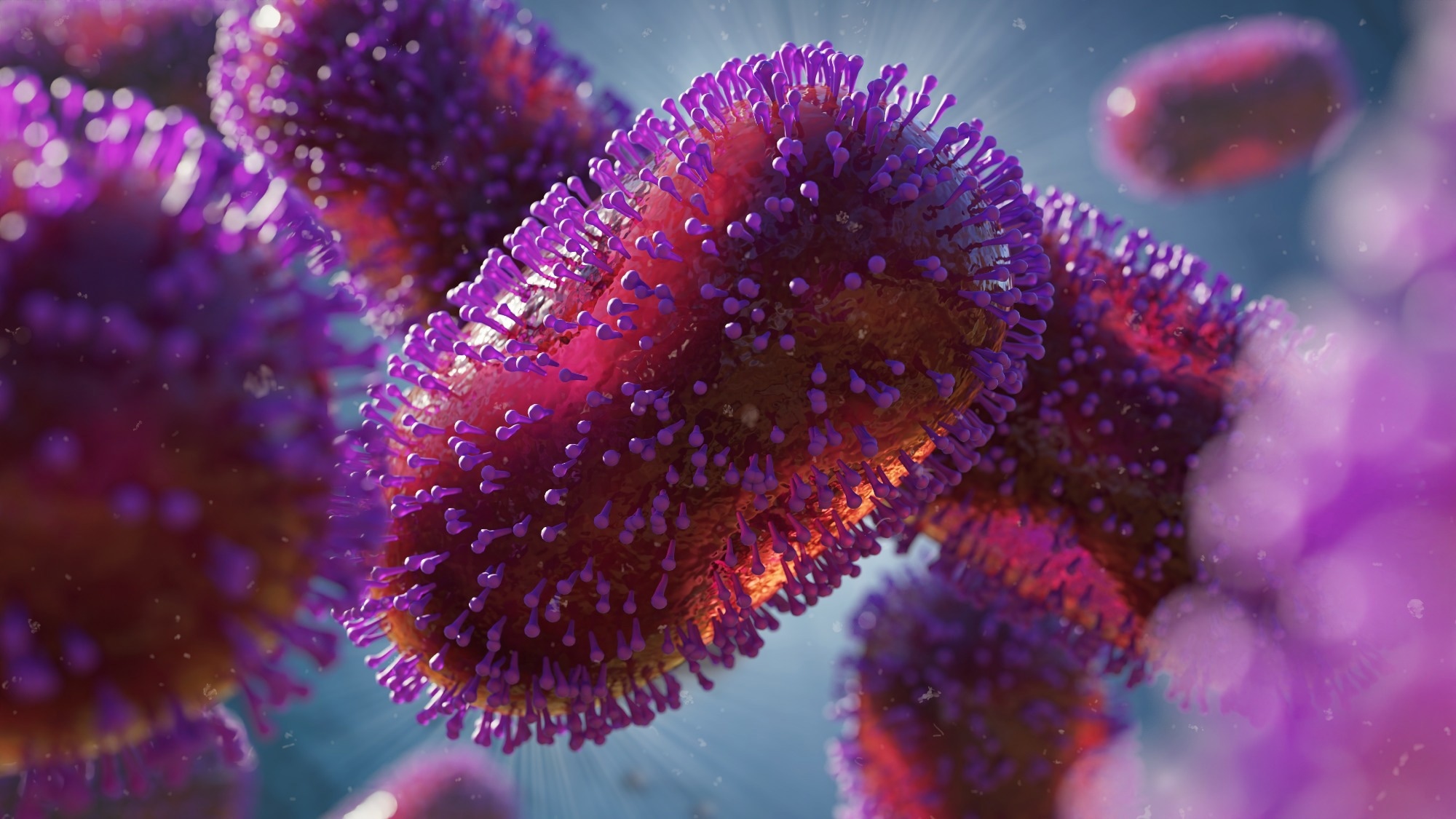

A large number of monkeypox cases were reported in 2022 outside the endemic areas in central and west Africa. The etiological agent of monkeypox is the monkeypox virus belonging to the Orthopoxvirus genus of the Poxviridae family, similar to the smallpox virus. It is a double-stranded deoxyribonucleic acid (DNA) virus, and its transmission among humans is thought to be primarily through contact with lesions, body fluids, and respiratory droplets.

Evidence of transmission among non-human primates through inhalation of aerosolized monkeypox virus indicates the potential for the disease to spread among humans via aerosolized respiratory droplets. Stable orthopox viruses have been detected in aerosols for almost 90 hours.

A case of monkeypox in a hospital worker in the United Kingdom (U.K.) was attributed to exposure while changing the bedding in the isolation room of a monkeypox patient. Furthermore, studies in Germany have reported widespread monkeypox virus contamination in hospital rooms housing monkeypox patients. These cases highlight the need to understand monkeypox transmission risk through environmental contamination.

About the study

In the present study, the researchers identified adult patients hospitalized at the Royal Free Hospital in London, U.K., with confirmed monkeypox cases and visible skin lesions. They sampled the air and surfaces in their isolation rooms after procuring informed consent. Air and surface swab samples were also collected from the external corridor and anterooms surrounding the isolation rooms and from the personal protective equipment (PPE) used by hospital staff tending to the monkeypox patients.

Swab samples were also collected from high-touch areas in the isolation room, such as the call bell, door handles, television remotes, light switches, tap handles, etc. Nucleic acid was isolated from the samples and tested using quantitative polymerase chain reaction (qPCR) for the presence of monkeypox DNA. Viral isolation from selected positive samples was carried out to confirm the presence of the monkeypox virus.

Results

The results reported that 93% (56 out of 60) of the swab samples tested positive for monkeypox virus DNA. The cycle threshold (Ct) values for the qPCR of the positive models indicated infection-competent levels of the monkeypox virus. One air sample during bedding change in the isolation room and one swab sample from the floor of the anteroom where PPEs were removed after use were positive for replication-competent monkeypox virus.

Swab samples from hard surfaces had lower Ct values (≤ 30), which can be explained by using hard-surface cleaners. Monkeypox virus contamination was also detected in swab samples from PPE and the fingertips of gloves after isolation room visits.

Contamination in air samples highlighted the need for effective respiratory protection equipment for the hospital staff who change beddings and carry out other assistive tasks for the monkeypox patients.

According to the authors, contamination of the environment and surfaces with the monkeypox virus, even replication-competent virus, is not enough to establish an infection in a person exposed to the virus. Host susceptibility, environmental factors that weaken the virus, transmission route, and the amount of viral exposure all contribute to successful infection.

The isolation areas that were tested were well-ventilated and regularly cleaned using 5000 to 10,000 parts per million chlorine sodium hypochlorite. The authors believe that the results could be different for other areas where the ventilation and disinfection procedures vary or where the patients are not present for prolonged periods, such as health clinics and outpatient areas. Therefore, further research is needed to understand how environmental contamination varies in hospital settings.

Conclusions

To summarize, the study investigated air and surface samples from isolation rooms of monkeypox patients, surrounding anterooms, and PPE worn by hospital staff attending to the patients for monkeypox virus contamination. The researchers found 93% of the samples to be contaminated with the virus, with two samples showing the presence of replication-competent viruses.

The results highlighted the need for more effective preventative measures, including efficient respiratory protection by hospital workers, to limit in-hospital transmission of monkeypox. Contamination of hard surfaces indicates potential transmission through fomites and emphasizes the use of stringent cleaning protocols and PPE.

- Gould, S., Atkinson, B., Onianwa, O., Spencer, A., Furneaux, J., Grieves, J., Taylor, C., Milligan, I., Bennett, A., Fletcher, T., Dunning, J., Dunning, J., Price, N., Beadsworth, M., Schmid, M., Emonts, M., Tunbridge, A., Porter, D., Cohen, J., & Whittaker, E. (2022). Air and surface sampling for monkeypox virus in a UK hospital: an observational study. The Lancet Microbe. doi: https://doi.org/10.1016/s2666-5247(22)00257-9 https://www.thelancet.com/journals/lanmic/article/PIIS2666-5247(22)00257-9/fulltext

Posted in: Medical Science News | Medical Research News | Disease/Infection News

Tags: Body Fluids, Contamination, CT, Disinfection, DNA, Healthcare, Hospital, Monkeypox, Nucleic Acid, Personal Protective Equipment, Polymerase, Polymerase Chain Reaction, PPE, Research, Respiratory, Skin, Smallpox, Virus

.jpg)

Written by

Dr. Chinta Sidharthan

Chinta Sidharthan is a writer based in Bangalore, India. Her academic background is in evolutionary biology and genetics, and she has extensive experience in scientific research, teaching, science writing, and herpetology. Chinta holds a Ph.D. in evolutionary biology from the Indian Institute of Science and is passionate about science education, writing, animals, wildlife, and conservation. For her doctoral research, she explored the origins and diversification of blindsnakes in India, as a part of which she did extensive fieldwork in the jungles of southern India. She has received the Canadian Governor General’s bronze medal and Bangalore University gold medal for academic excellence and published her research in high-impact journals.

Source: Read Full Article