New treatment combination could work against broader array of cancer cells, study finds

In continuing efforts to find novel ways to kill cancer cells, researchers at the University of Maryland School of Medicine (UMSOM) have identified a new pathway that leads to the destruction of cancer cells. The new finding, published this week in the journal PNAS, could pave the way for the broader use of a class of anticancer drugs already on the market. These drugs, known as PARP inhibitors, are currently approved by the FDA to treat only a limited group of breast and ovarian cancers associated with BRCA gene mutations.

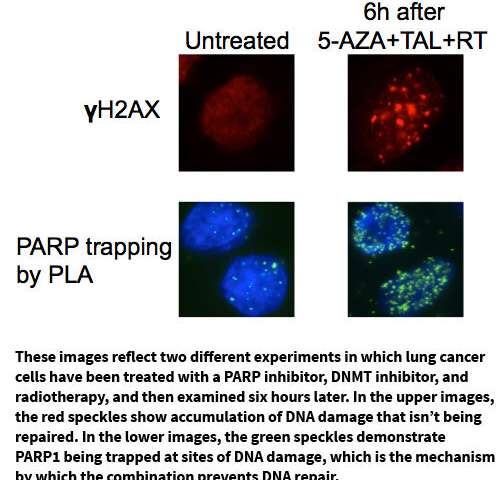

In a proof of concept study, the researchers demonstrated that combining a PARP inhibitor with a DNA methyltransferase (DNMT) inhibitor delivered a one-two punch to non-small cell lung cancer tumors, which are normally not associated with mutations in BRCA genes. The research, conducted in mouse models and cell lines, outlines the mechanistic action of the combination. The DNMT inhibitor triggers an effect that mimics a BRCA mutation in the cancer cell so the cell responds to the lethal effects of the PARP inhibitor, which prevents repair of damage to a tumor cell’s DNA, triggering cell death.

“When combined, these agents cause interactions that significantly disrupt cancer cells’ ability to survive DNA damage,” said study senior author, Feyruz V. Rassool, Ph.D., professor of radiation oncology at UMSOM. “Our findings could expand the use of PARP inhibitors beyond the minority of inherited cancers that it now treats.”

Those who inherit two copies of a normal BRCA gene enjoy protection from DNA damage that can cause healthy cells to turn malignant. Those who inherit a mutation in this gene, however, have a higher risk of breast and ovarian cancer (in women) and prostate cancer (in men). Researchers have previously demonstrated that tumors that share molecular features of BRCA-mutant tumors—those with so-called “BRCAness”—respond to PARP inhibitor drugs designed to target tumors that arise from BRCA mutations. This new study from UMSOM is the first to demonstrate that cells can be induced to have a BRCAness phenotype or gene expression that is not the result of a mutation by treating them with the DNA methyltransferase inhibitor drug.

DNMT inhibitors suppress DNA methylation, which leads to changes in gene expression that significantly interfere with cancer cell growth. They are FDA-approved for use in myelodysplastic syndromes (cancers of the bone marrow),but are not usually combined with PARP inhibitors. Stephen Baylin, MD, Chief of Cancer Biology at Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine and graduate student Michael Topper at Johns Hopkins University, key collaborators in this study, have expertise in the action of these drugs.

The researchers also found that the DNMT and PARP inhibitor combination prevented cancer cells from repairing the DNA damage caused by radiation, a common treatment for lung cancer. “We are very excited by the new finding because it explains the mechanistic action of this drug combination, which we found has a synergistic effect, and so works better than either drug alone,” said Rachel Abbotts, MD Ph.D., a postdoctoral fellow in the Department of Radiation Oncology who is the first author of the paper. “When we combined with radiation therapy, which is the standard treatment for lung cancer, we measured an even bigger effect.”

The researchers are now aiming to test this protocol in an early phase trial in patients with non-small cell lung cancer that will be conducted in coordination with the Marlene and Stewart Greenebaum Comprehensive Cancer Center. Two years ago, Dr. Rassool and her research team demonstrated that this novel drug combination worked to disrupt cancer cells in acute myeloid leukemia and they are now testing the protocol in a trial of cancer patients with AML. Early results suggesthat this drug combination is well tolerated.

Source: Read Full Article