History of Tuberculosis

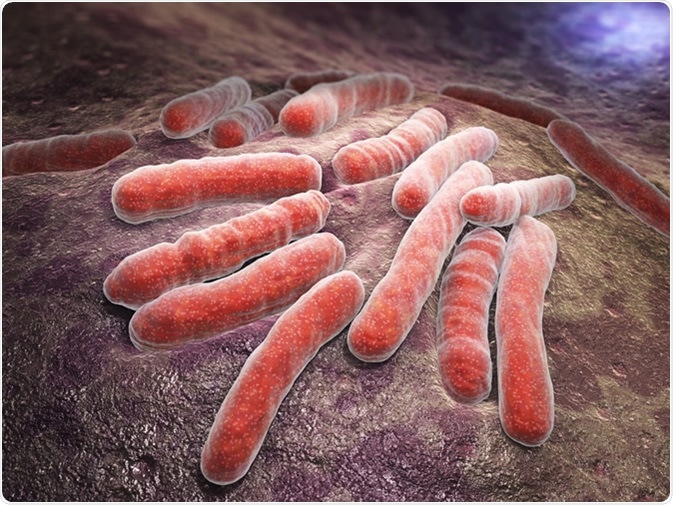

Tuberculosis is a highly contagious disease caused by the bacteria Mycobacterium tuberculosis (M. tuberculosis), which is believed to be present in the nature for at least 15,000 years.

Tuberculosis has been known to mankind since ancient times. It is believed that the genus Mycobacterium was present in the environment about 150 million years ago, and an early variant of M. tuberculosis was originated in East Africa about 3 million years ago. A growing pool of evidence suggests that the current strains of M. tuberculosis is originated from a common ancestor around 20,000 – 15,000 years ago.

Studies on Egyptian mummies (2400 – 3400 B.C) revealed the presence of skeletal deformities related to tuberculosis, such as characteristic Pott's deformities. However, no evidence on tuberculosis was found in Egyptian papyri. The description of tuberculosis was initially found in India and China as early as 3300 and 2300 years ago, respectively. Moreover, tuberculosis was mentioned in the Biblical books using the Hebrew word ‘schachepheth’ to describe tuberculosis.

In the Andean states, the first pre-Columbian evidence of tuberculosis was observed in Peruvian mummies, indicating the presence of the disease before the European colonization in South America.

Tuberculosis was well documented in the Ancient Greece as ‘Phthisis’ or ‘Consumption’. In Book I, Of the Epidemics, Hippocrates described the symptoms of Phthisis, which are very much similar to the common characteristics of tubercular lung lesions.

A Greek physician, Clarissimus Galen, who became the physician of the Roman Emperor Marcus Aurelius in 174 AD, described the symptoms of tuberculosis as fever, sweating, coughing and blood-stained sputum. He also suggested that an effective treatment of tuberculosis should include fresh air, milk, and soy beverages.

In Roman times, tuberculosis was mentioned by Celso, Aretaeus of Cappadocia, and Caelius Aurelianus. However, it remained unrecognized at that time. After the decline of the Roman Empire in the 5th century, a vast pool of archeologic evidence of tuberculosis was found throughout Europe, indicating that the disease was widespread in Europe during this time.

In the Middle Ages, a new clinical form of tuberculosis was described as scrofula, which is a disease of cervical lymph nodes. In England and France, the disease was known as ‘king’s evil’, and there was a popular believe that the disease can be treated with the ‘royal touch’. The practice of the ‘royal touch’ established by English and French kings continued for several years. Queen Anne was the last British monarch to employ this method for healing.

The first medical intervention for treating tuberculosis was proposed by a French surgeon, Guy de Chauliac. He advised the removal of scrofulous gland as a treatment option.

In the 16th century, a clear description about the contagious nature of tuberculosis was first provided by an Italian physician, Girolamo Fracastoro.

In 1679, Francis Sylvius provided the exact pathological and anatomical description of tuberculosis in his book ‘Opera Medica’. In 1720, a British physician, Benjamin Marten, first described the infectious origin of tuberculosis in his publication entitled ‘A new theory of Consumption. In the 17th and 18th centuries, the terms ‘Consumption’ and ‘phthisis’ were used to describe tuberculosis.

In 1819, a French physician, Theophile Laennec, identified the pathological signs of tuberculosis, including consolidation, pleurisy, and pulmonary cavitation. He also identified that M. tuberculosis can infect the gastrointestinal tract, bones, joints, nervous systems, lymph nodes, genital and urinary tracts, and skin (extra-pulmonary tuberculosis), in addition to the respiratory tract (pulmonary tuberculosis).

In 1834, Johann Schonlein first coined the term ‘tuberculosis’. At the beginning of the 19th century, there was a scientific debate about the exact etiology of tuberculosis. Many theories existed that time, describing the disease as an infectious disease, a hereditary disease, or a type of cancer.

In 1843, Philipp Friedrich Hermann Klencke, a German physician, experimentally produced the human and bovine forms of tuberculosis for the first time by inoculating extracts from a miliary tubercle into the liver and lungs.

In 1854, sanatorium cure for tuberculosis was introduced by Hermann Brehmer, a tuberculosis patient, in his doctoral thesis. He mentioned that a long-term stay in the Himalayan mountains helped cure his tuberculosis.

A French military surgeon, Jean-Antoine Villemin, experimentally proved the infectious nature of tuberculosis in 1865. He inoculated a rabbit with fluid taken from a tuberculous cavity of a person who died of tuberculosis.

A German physician and microbiologist, Robert Koch, successfully identified, isolated, and cultured the tubercle bacillus in animal serum. Afterward, he produced animal models of tuberculosis by inoculating the bacillus. In 1882, his groundbreaking work was published in the Society of Physiology in Berlin.

Discovery of diagnostic methods

In 1907 – 1908, Clemens von Pirquet and Charles Mantoux developed the tuberculosis skin test wherein tuberculin (extracts of the tuberculosis bacillus) is injected under the skin, and body’s reaction was measured. In recent years, advancement in tuberculosis diagnosis includes interferon-gamma release assays, which are whole-blood tests to detect M. tuberculosis infection.

Discovery of vaccine

A pioneering work toward the prevention of tuberculosis was made by Albert Calmette and Jean-Marie Camille Guerin, who developed the Bacille Calmette-Guérin (BCG) vaccine in 1921.

Discovery of therapeutic agents

Besides preventive vaccines, a major breakthrough in tuberculosis treatment occurred with the discovery of antibiotics. In 1943, a tuberculosis antibiotic streptomycin was developed by Selman Waksman, Elizabeth Bugie, and Albert Schatz. Afterward, Selman Waksman received the Nobel prize in 1952.

In the recent era, four antibiotics namely isoniazid (1951), pyrazinamide (1952), ethambutol (1961), and rifampin (1966) are used to effectively treat tuberculosis. With the improvement in diagnostic procedures, therapeutic interventions, and preventive strategies, the World Health Organization (WHO) has committed to eradicate M. Tuberculosis by the year 2050.

Sources

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. 2018. World Tuberculosis Day. https://www.cdc.gov/tb/worldtbday/history.htm

- Barberis I. 2017. The history of tuberculosis: from the first historical records to the isolation of Koch's bacillus. Journal of Preventive Medicine and Hygiene. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC5432783/

- Daniel TM. 2006. The history of tuberculosis. Respiratory Medicine. https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S095461110600401X

Further Reading

- All Tuberculosis Content

- What is Tuberculosis?

- Tuberculosis Causes

- Tuberculosis Diagnosis

- Tuberculosis Prevention

Last Updated: Sep 16, 2019

Written by

Dr. Sanchari Sinha Dutta

Dr. Sanchari Sinha Dutta is a science communicator who believes in spreading the power of science in every corner of the world. She has a Bachelor of Science (B.Sc.) degree and a Master's of Science (M.Sc.) in biology and human physiology. Following her Master's degree, Sanchari went on to study a Ph.D. in human physiology. She has authored more than 10 original research articles, all of which have been published in world renowned international journals.

Source: Read Full Article