Atherosclerosis: How the body controls the activity of B cells

LMU researchers have identified a protein that is involved in the regulation of immune cells and can curb the development of atherosclerosis. Their research is published in Nature Cardiovascular Research.

Cardiovascular diseases related to atherosclerosis are the leading cause of death worldwide. In patients, the body deposits cholesterol esters and other fats in the inner wall of arteries. This results in the build-up of plaques, which can constrict the flow of blood so strongly that the oxygen supply to organs is impaired. Researchers have known for some time that chronic inflammatory processes occur in atherosclerosis.

A type of white blood cell known as the B cell appears to play an important role as part of the adaptive immune response. B cells have both protecting and damaging effects through the medium of antibodies. In other words, they can either promote or inhibit atherosclerosis. But how exactly does the body regulate which of these processes takes effect?

Researchers led by Prof. Sabine Steffens from the Institute for Cardiovascular Prevention (IPEK) have now identified a protein that plays a crucial role in controlling the adaptive immune response in atherosclerosis. The scientists think this protein could be suitable as a target for innovative therapies.

The role B cells play in atherosclerosis

“We wanted to understand better how B cells influence atherosclerotic diseases, with the long-term goal of developing novel therapies centered on B cells for this life-threatening condition,” says Steffens, outlining the objectives of her research project. She was particularly interested in the receptor GPR55, which forwards chemical signals from the exterior to the interior of cells.

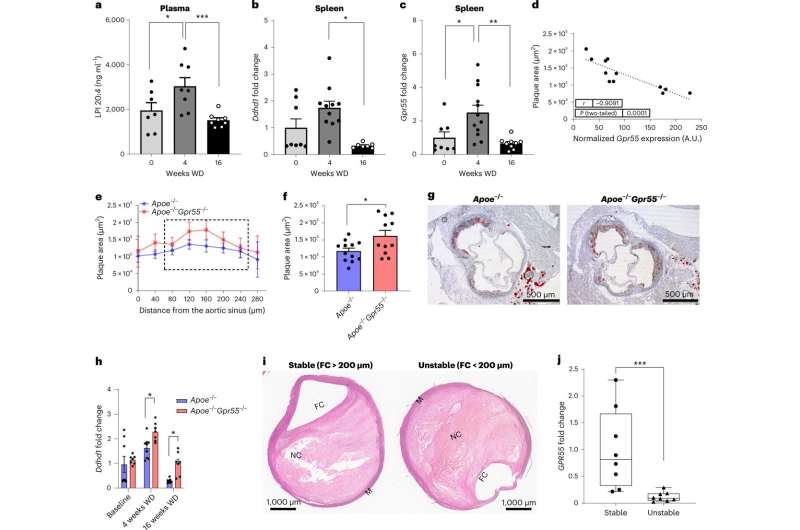

B cells in the spleen of mice produce the molecule in large quantities. For their study, the scientists investigated mouse models for atherosclerosis. If the mice received special food to trigger atherosclerosis, the receptor was upregulated after only a month—which is to say, at a rather early stage of the disease. Mice that are unable to produce GPR55 developed larger atherosclerotic plaques compared to the wild type. In these mice, B cells were over-activated without GPR55 and inflammatory processes were promoted accordingly.

When the researchers investigated human atherosclerotic plaques, they discovered that less receptor was present in unstable plaques with a high risk of triggering a stroke compared to stable plaques. “This finding indicates that the expression of the protein changes over the course of the disease,” reports Steffens.

Source: Read Full Article