Black and Hispanic adults faced disparities in initial heart attack care

Significant differences in initial heart attack diagnosis and treatment were found among Black and Hispanic adults compared to white adults, according to new research published in the open access, peer-reviewed Journal of the American Heart Association.

“An American Heart Association presidential advisory and the Center for Disease Control’s Healthy People 2030 initiative have asserted that addressing racial disparities is a priority, yet there is still more work to be done regarding the persistent racial and ethnic disparities in the management of heart disease,” said Tarryn Tertulien, M.D., M.Sc., lead author of the study and a resident in internal medicine at the University of Pittsburgh Medical Center.

Researchers examined 2017–2019 health claims of more than 87,000 people (average age 74 years, 56% men) diagnosed with non-ST Elevation Myocardial Infarction (NSTEMI), a type of heart attack in which an artery is partially blocked and severely reduces blood flow. The data evaluated was from Optum Clinformatics Data Mart, an administrative database including inpatient, outpatient, emergency department, pharmacy and lab health insurance claims from people with commercial health insurance and Medicare Advantage insurance. The database categorized participants by race and ethnicity: Asian (2.6%), Black (13.4%), Hispanic (11.2%) or white (72.7%). Additional factors considered included age, sex, the number of other medical conditions present, educational level, health insurance type and annual household income (ranging from less than $40,000 annually to more than $100,000 annually).

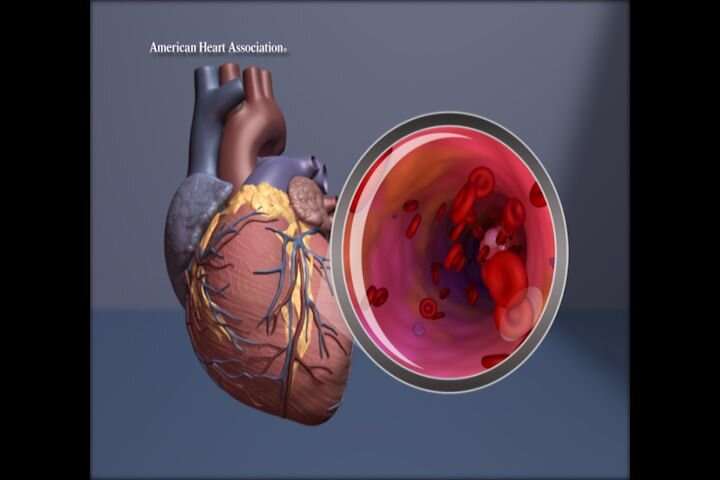

The investigators analyzed racial and ethnic differences in the use of two procedures: coronary angiography and percutaneous intervention (PCI). Coronary angiography is a diagnostic procedure that uses a dye and X-rays to visualize blood flowing through the coronary arteries to determine if a blockage in one or more arteries is causing the heart attack. PCI is a minimally invasive method of threading a slim hollow tube from a blood vessel in the arm or thigh until it reaches the blockage and opening the artery by inflating a balloon at the tube’s tip. The artery may be held open with a small, permanent tube called a stent.

According to the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association’s 2021 guidelines, people with NSTEMI require intervention for worsening sudden chest pain, heart failure, anatomical abnormalities and other conditions. When NSTEMI results from a blockage, the standard of care is to restore blood flow by opening the affected area of the artery.

This analysis found:

- Compared with white adults in the study, Black adults were 7% less likely to undergo coronary angiography and 14% less likely to have PCI;

- Compared with white adults, Hispanic adults were 12% less likely to undergo coronary angiography and 15% less likely to have PCI;

- There was no significant difference in the rate of coronary angiography or PCI between Asian patients and white patients; and

- Although all people in the study had medical insurance (either private or Medicare Advantage), those who had lower annual household incomes within each racial and ethnic group were less likely to receive coronary angiography.

“Knowing the increased awareness of health disparities, we were surprised that the racial disparities persisted in present-day data,” Tertulien said.

Disparities in medical treatment can be addressed at both an individual and a policy level.

“Physicians have three essential responsibilities,” said senior study author Jared W. Magnani, M.D., M.Sc., an associate professor of medicine at the University of Pittsburgh. “First, they must practice medicine that is blind to race and ethnicity, providing the same standard of care regardless of gender, race, ethnicity or other social factors. Second, they must understand how patients’ life experiences—due to structural factors, racism, financial obstacles and other social determinants—may influence risk factors, access to care and how serious their condition is at presentation. Third, they must be aware of their personal biases, which may influence their ability to provide equitable care.”

The study is limited by its reliance on the administrative coding of diagnoses and procedures, making it impossible to factor in variables such as people’s symptoms and the results of coronary angiography. Because the study was conducted using the records of people with health insurance, the findings may not be generalizable to an uninsured population.

Source: Read Full Article