Nurses as parents exemplify link between poor sleep and daily stress, study shows

A new paper in the peer-reviewed Journal of Sleep Research details how nurses who also are parents might be more susceptible than other groups to daily stress aggravated by poor sleep. The consequences of the sleep-stressor link in nurses with children may affect their caregiving at home and on the job, where nurses represent the largest population of front-line health care workers.

“We were really interested in looking at how the sleep-stressor relationship is different for nurses who are parents and nurses who are not parents,” said lead author Taylor Harris, doctoral student in counseling psychology at the University of Kansas. “We also wanted to look at how many children parents have further influences the relationship between sleep and stress in those working parents, because caregiving at work and at home can be particularly difficult—sometimes we don’t always look at that intersection specifically in the most prominent health care profession, which is nursing.”

Harris and her co-authors, Taylor F. D. Vigoureux and Soomi Lee of the University of South Florida, recruited 60 nurses—both parents and nonparents—and asked them to track their sleep and stress levels on smartphones for two weeks between May and September 2019.

“We had a background survey that was distributed during the informed-consent meetings including just very basic demographic and work characteristics—nurses were full-time inpatient workers, either on the day shift or night shift,” Harris said. “Then, for 14 days, participants responded to these brief surveys on their smartphones. We had them answer questions upon waking and then three times daily in order for us to collect the data we needed. Sleep questions were included in the upon-waking survey, and the daily stressor questions were included in the three following surveys.”

The research confirmed a long-established truth in such studies: Parents are more likely to suffer from worse sleep compared with people without kids.

“We all kind of know that people who are parents have poorer overall sleep,” Harris said. “That could be from the demands of having to take children to appointments, or in general to attend to needs outside of their own—that can be changing diapers, feeding, eating or worrying about children that are older and getting into college to worrying about how children progress from childhood to adulthood. People who are parents do tend to have that additional burden of having a harder time sleeping.”

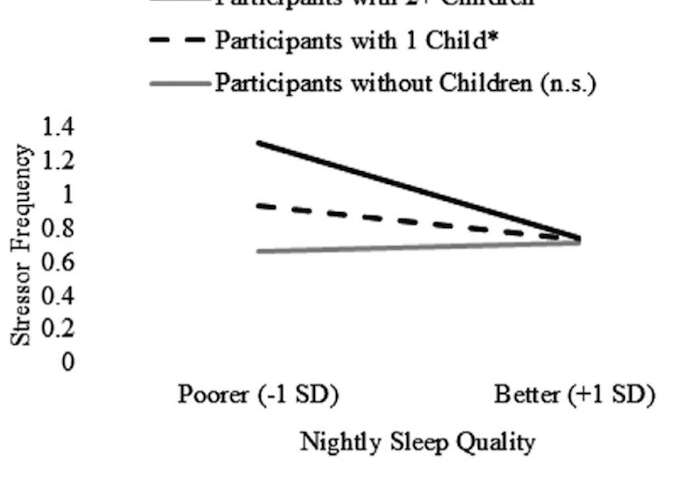

The study showed this is especially the case with nurses: Poorer-than-usual sleep quality was associated with more frequent and more severe stressors the following day for parent nurses with one child and two or more children, but not for nonparents. Further, the link between sleep quality and daily stressors became greater as the number of children at home increased.

“The most striking findings were when looking at nightly sleep quality and stressor frequency and then nightly sleep quality and stressor severity,” Harris said. “We see how the participants who were parents had this stronger linkage between poor sleep and frequency and severity of stress, showing how for this population of nurses—all either day shift or night shift workers—being a parent really exacerbates that link.”

According to the American Nurses Association, stress is one of the “most impactful issues nurses face.” The ANA reports this stress can worsen the health of nurses themselves and patient outcomes—as well as nurses’ ability to stay in the profession and the financial health of organizations in the health care industry.

“For nurses, poor sleep can lead to not as much cognitive functioning the next day, as well as poor work performance with less of an ability to stay on task,” Harris said. “Then that further transcends into all areas of life, both work and home, and even can hurt that caregiving role that is so important in that parent-child relationship.”

The KU graduate student said health care businesses and organizations could work to lessen the stress of nursing and develop programs to improve the nurses’ sleep, especially for nurses who also have children.

“Sometimes we don’t think about the sleep-stressor link, and that can be really important in terms of intervention purposes for nurses who are parents, so that they can in turn be both better workers and better parents,” Harris said. “Caregiving both at home and work is really difficult and being able to provide whatever type of intervention that would help nurses sleep better would then help lower those stressor frequencies and severity of stressors and, in turn, promote better cognitive performance at work and just better quality of life overall.”

Source: Read Full Article