Too much or not enough: The health care dilemma in developing countries

Globalization has significantly improved access to quality health care but some patients in developing countries are getting too much of it, researchers say.

A series of scoping reviews into overdiagnosis and overuse of health care services reveal the problems of too much medicine—already well-established in high-income countries—are now widespread in low and middle-income countries (LMICs).

Dr. Loai Albarqouni and Dr. Ray Moynihan of Bond University worked with a team of 30 researchers from 15 countries to summarize the evidence.

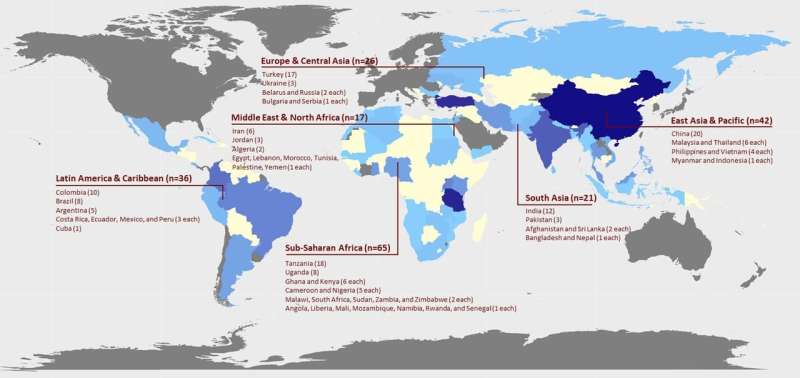

The first results, published in the BMJ Global Health journal and the Bulletin of the World Health Organization, are based on more than 500 scientific articles involving almost eight million participants or health care services in 80 LMICs.

Among the findings:

- An analysis of 5 million patients found high rates of thyroid cancer in some LMICs. However, death rates from thyroid cancer had remained low, strongly suggesting tiny thyroid tumors are unnecessarily being diagnosed and treated as cancer.

- A study of more than 3,000 patients from 95 health centers in Sudan found a growing recognition of malaria overdiagnosis and calculated that this wasted US$80 million in the year 2000.

- In 2014 in Iran, a study found half of the requests for magnetic resonance imaging for low back pain were inappropriate or unnecessary. Another study from 2021 in Iran estimated the cost of inappropriate use of brain imaging in just three teaching hospitals to be greater than US$100,000.

- In Lebanon, a 2020 study found massive overuse of stomach drugs called proton pump inhibitors, with two in three people taking them unnecessarily. Approximately US$25 million was wasted annually.

- A large global study in 2020 examined antibiotic use among more than 65,000 children under five in Haiti, Kenya, Malawi, Namibia, Nepal, Senegal, Tanzania, and Uganda. Antibiotics were prescribed to more than 80% of children diagnosed with respiratory illness and most of these prescriptions were deemed unnecessary.

Dr. Albarqouni, an Assistant Professor at Bond University’s Institute for Evidence-Based Healthcare, said the studies were the first of their type.

“They show solutions are already being tested, though not often enough,” he said.

“One example is a large study in Ghana which found that introducing new rapid diagnostic tests could halve the rates of unnecessary treatment for malaria.”

Dr. Albarqouni said too much medicine often existed side-by-side with underuse in LMICs.

One large study covering 70 LMICs found huge inequality in rates of cesarean sections. While the poorest people had inadequate access to emergency cesarean sections, the richest could obtain them even when they were not needed.

Dr. Moynihan, an Assistant Professor at the Institute for Evidence-Based Healthcare, said there were plans to build on the results of the reviews and create a global alliance to reduce overdiagnosis and overuse of health care services in LMICs.

“This collaborative effort could further understand the problems and develop and evaluate potential solutions,” he said.

Overdiagnosis and overuse are common in high-income countries. The Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development estimates about 20 percent of health care spending may be wasted.

Researchers at Bond University’s Institute for Evidence-Based Healthcare helped initiate the international scientific conference Preventing Overdiagnosis. The conference has been co-sponsored by the World Health Organization, and the next one will happen in Denmark in 2023.

More information:

Loai Albarqouni et al, Overdiagnosis and overuse of diagnostic and screening tests in low-income and middle-income countries: a scoping review, BMJ Global Health (2022). DOI: 10.1136/bmjgh-2022-008696

Bulletin of the World Health Organization paper (doc)

Journal information:

Bulletin of the World Health Organization

,

BMJ Global Health

Source: Read Full Article