Scientists map brain circuit that drives activity in fertile females

Scientists have known for a century that female animals become more active just as they are about to ovulate, a behavior that evolved to enhance their chances of mating when they are fertile.

Now, a team at UC San Francisco has identified the specific neurons and signaling pathway that make sexually receptive females of many species run around at this critical time. The work was done in mice, but researchers expect it will bear out in humans, since the behavior is related to such a fundamental aspect of life.

“Why do you want to get up and move?” asked Holly Ingraham, Ph.D., the Herzstein Professor of Molecular Physiology at UCSF and senior author of the study published in Nature. “Well, if you activate the circuit in these neurons, maybe that’s why.”

The discovery also illuminates what happens in menopause as the loss of estrogen disrupts this activity circuit, and both mouse and human females become more sedentary, gain weight, and develop metabolic disorders like type 2 diabetes. And it offers the possibility of a new kind of treatment for menopause that sidesteps estrogen and reactivates the circuit with CRISPRa technology.

“As we discover what estrogen does in the brain, we’re probably going to discover more of its benefits,” Ingraham said. “This is just one area in the brain, and it has a powerful effect. We’d also like to know more about other circuits in the brain that affect well-being and cognition.”

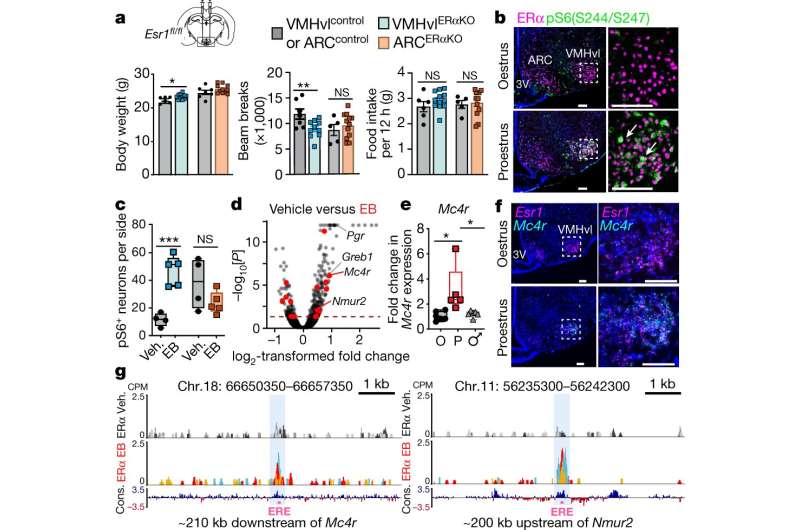

When estrogen bathes the brain, it interacts with estrogen receptor α (ERα) to activate a gene called Mc4r. This produces melanocortin-4 receptors (MC4R) on the surface of estrogen-sensitive neurons in a part of the brain called the ventrolateral ventromedial hypothalamic nucleus (VMHvl) that regulates how energy is used in adult females.

The study team created a precise map of where proteins attach to DNA, using technology established in the living mouse brain by co-senior author Jessica Tollkuhn, Ph.D., an assistant professor at Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory in New York. The technique, called CUT&RUN or cleavage under targets and release using nuclease, identified two sites where ERα binds to Mc4r to regulate its activity, thus establishing a clear link between the hormone receptor and the gene.

To their surprise, the team also discovered that the VMHvl neurons activated by this circuit project into a part of the hippocampus equipped with “speed cells” that control how fast the mouse moves. The neurons also project into a region of the hindbrain that mediates sexual receptivity and physical activity.

The gene at the center of this circuit, Mc4r, is well known for its role in regulating energy, appetite, and weight in adult females, and mutated forms of the gene cause obesity that are particularly severe in women.

The MC4R receptor is also the target of bremelanotide, which is marketed under the brand name Vyleesi to treat a condition called acquired, generalized hypoactive sexual desire disorder (HSDD) in premenopausal women.

To be sure the neurons really were making the mice more active, the researchers used a chemogenetic technique called DREADDs (Designer Receptors Exclusively Activated by Designer Drugs) to make the VMHvl neurons express a receptor that could only be activated by a harmless chemical added to their water.

When their VMHvl neurons were stimulated that way, both male and female mice became more active, and the females lost nearly 10 percent of their body weight after 24-hours of continuous administration. Inhibiting these neurons had the opposite effect, making females more sedentary.

The same thing happened in female mice that lacked ovaries and had been put on a high-fat diet. A single instance of DREADD stimulation reversed the harmful metabolic effects of both estrogen depletion and diet-induced obesity. Long-term administration caused obese mice to slim down dramatically, and it improved their overall metabolic health.

The team also used CRISPRa, a technique that upregulates gene expression without changing the gene itself, to increase the activity of Mc4r. Both male and female mice became more active, but the effects were stronger in females, and their bones grew thicker. They did not lose weight, however, most likely because they also ate more.

“These data are exciting not only because they highlight the key role of Mc4r in these activity-promoting neurons, but because they also suggest how gene therapy tools might be adapted to target advantageous factors downstream of estrogen signaling,” said first author William Krause, Ph.D., a researcher in the Department of Cellular and Molecular Pharmacology at UCSF.

The beneficial results add to the debate over hormone replacement therapy for symptoms of menopause. Many doctors stopped prescribing it after an influential 2002 study found it slightly increased the risk of endometrial and breast cancer, as well as blood clots and stroke.

But Ingraham said it’s worth another look.

Source: Read Full Article