Fighting the herpes virus

New insights into preventing herpes infections have been published in Nature Communications. Researchers from the Berlin Institute for Medical Systems Biology (BIMSB) at the MDC used single-cell RNA sequencing to better understand the viral infections.

If your lip starts to tingle and itch, it often means that you’re about to get a cold sore, a small, painful blister filled with the highly contagious herpes simplex virus (HSV). About 80 percent of the global population carries the herpes simplex virus type 1 (HSV-1). Once a person contracts the virus, it remains in the body for the rest of their life, and usually goes entirely unnoticed. In rare cases, such as in newborns or people with weak immune systems, the herpes virus can cause inflammation of the brain or lungs.

Now, a group of researchers is examining exactly what happens inside individual cells during an infection. The head of the team is Professor Markus Landthaler of the Berlin Institute for Medical Systems Biology (BIMSB) at the Max Delbrueck Center for Molecular Medicine (MDC). Emanuel Wyler and Vedran Franke are the two lead authors of the study on HSV-1 infections, which has been published in the open-access journal Nature Communications.

Inhibiting the herpes infection

At BIMSB, bioinformatician Franke develops algorithms that allow him to predict the probability of infection progressing in individual cells. Wyler and Franke wanted to know exactly what might encourage or slow the infection. They investigated differences in the way the infection progresses in individual cells and found that the NRF2 transcription factor plays a major role. The authors say that NRF2 activation slows the progress of the infection.

“I visualized changes in the regulation of each gene we investigated in a single cell. This showed us that the activation level of the NRF2 transcription factor can be a marker for temporary resistance to HSV-1 infection,” says Franke. The condition of the cell also seems to be decisive. They found that a cell is more vulnerable to HSV-1 infection during some phases of the cell cycle than others.

The study also presents another finding: A drug that is currently being tested for patients with chronic kidney disease could inhibit herpes infection by activating the NRF2 transcription factor. When the herpes virus enters host cells, it brings its own genetic information with it. This means that both human and virus genes are activated in the infected cells. When the team treated these cells with the kidney drug—bardoxolone methyl—the virus became less productive. It activated fewer of its own genes, which would normally fuel the infection. The authors believe this is due to the drug’s effect on the NRF2 transcription factor.

Precise data thanks to single-cell RNA sequencing

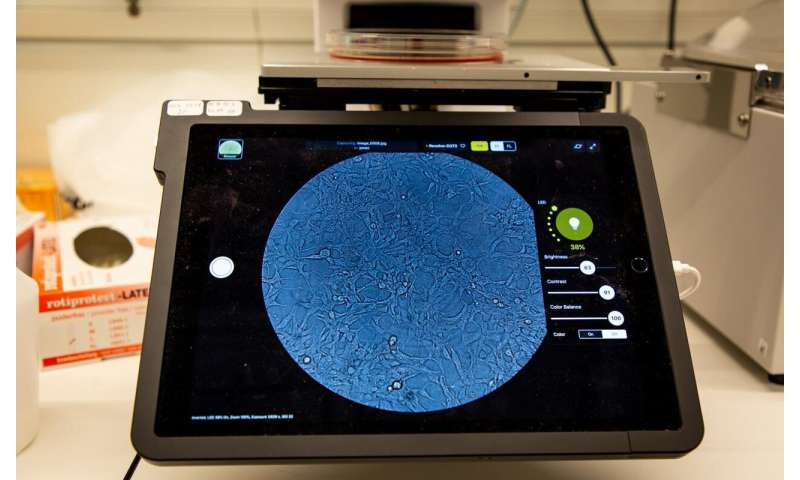

To date, few researchers have investigated an acute viral infection as comprehensively as the BIMSB team. Its work relies on a method that has been in use at the MDC since 2016: single-cell RNA sequencing. Conventional sequencing would allow the researchers to find out which genes in the investigated cells were active on average, but differences in the cells would not be visible. The information produced with these methods is a bit like a fruit smoothie: “If I put 10 types of fruit into a blender, I can roughly tell that the smoothie contains, say, blackberries when I taste it,” says Wyler. “With single-cell RNA sequencing, we aren’t making a smoothie—we’re making a fruit salad. I can immediately identify the blackberries and say exactly how many are in the salad.”

Wyler and Franke collaborated very closely to understand and compare the data. In the lab, the team investigated about 12,000 human skin cells infected with HSV-1. For each cell, the new sequencing method produced a separate data set containing information about the activated genes. “If you’ve got 12,000 cells and 3,000 analyzed genes, then looking at a huge excel spreadsheet isn’t going to be much help,” says Wyler.

Researchers have previously used conventional RNA sequencing to identify roughly 70 HSV-1 genes that are activated in the host cell. Up until now, says Wyler, it was only known that the genes US1 and UL54 are active in a group of cells at the same time. The new study shows that some cells activate only one of the two genes—”but we don’t know why just one of them is activated.” Wyler and Franke say that all the results presented in their paper were only possible with single-cell RNA sequencing.

Blueprint for further research

Source: Read Full Article