Charting hidden territory of the visual sensory thalamus

Neuroscientists at Technische Universität Dresden discovered a novel, non-invasive imaging-based method to investigate the visual sensory thalamus, an important structure of the human brain and point of origin of visual difficulties in diseases such as dyslexia and glaucoma. The new method could provide an in-depth understanding of visual sensory processing in both health and disease in the near future.

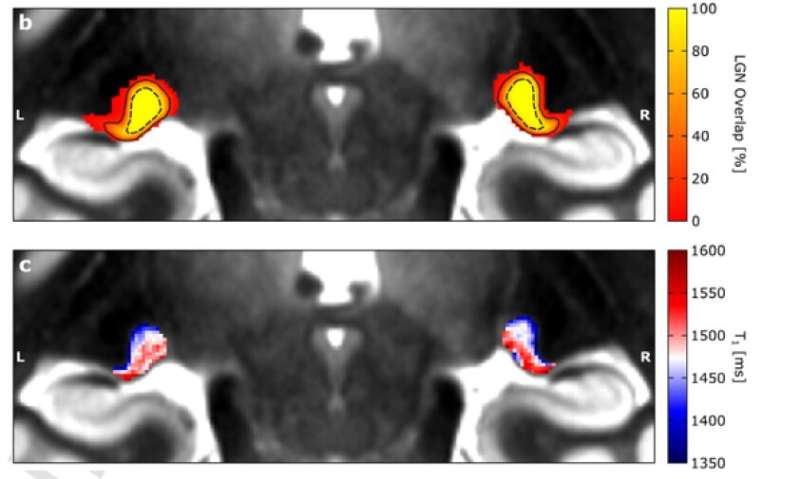

The visual sensory thalamus is a key region that connects the eyes with the cerebral cortex. It contains two major compartments. Symptoms of many diseases are associated with alterations in this region. So far, it has been very difficult to assess these two compartments in living humans, because they are tiny and located very deep inside the brain.

This difficulty of investigating the visual sensory thalamus in detail has hampered the understanding of the function of visual sensory processing tremendously in the past. By coincidence, Christa Müller-Axt, Ph.D. student in the lab of neuroscientist Prof. Katharina von Kriegstein at TU Dresden, discovered structures that she thought might resemble the two visual sensory thalamus compartments in neuroimaging data. The neuroimaging data was unique because it had an unprecedented high spatial resolution obtained on a specialized magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) machine at the MPI-CBS in Leipzig, where the group was researching developmental dyslexia. She followed up this discovery in a series of novel experiments involving analysis of high spatial resolution in-vivo and post-mortem MRI data as well as post-mortem histology and was soon sure to have discovered the two major compartments of the visual sensory thalamus.

The results showed that the two major compartments of the visual sensory thalamus are characterized by different amounts of brain white matter (myelin). This information can be detected in novel MRI data and thus, can be used to investigate the two compartments of the visual sensory thalamus in living humans.

Source: Read Full Article