\u2018This Isn\u2019t How Straight Couples Are Treated\u2019

When Amanda Roth first walked into a fertility clinic in 2011, her situation wasn’t exactly like that of the many other patients in the waiting room. She hadn’t been trying to conceive with a male partner for some time; as someone with a female partner, she simply didn’t have sperm at home.

Queer and lesbian couples can get past that biological hurdle with one of two options: insemination with donor sperm or reciprocal IVF, a method in which one woman’s eggs (fertilized by donor sperm) are transferred into the other partner’s uterus to carry. Visiting a fertility clinic is one way for queer women to get the ball rolling on one of those options; but it doesn’t necessarily mean they’re concerned about being able to conceive.

Despite having different needs when it comes to fertility care, they’re often treated just like the straight women in the clinic. Research bears this out: Current guidelines recommend that male-female couples with no known fertility problems pursue medical interventions only after failure to conceive for one year (or six months, in the case of women over 35).

There are no such guidelines for lesbian and queer women, which means they’re often advised to undergo hormonal testing, take fertility-boosting medication, or pursue IVF without any indication that they would have trouble getting pregnant with donor sperm, per a study from the journal Fertility and Sterility. The research was led by Roth, a PhD and assistant professor of philosophy and women’s studies at State University of New York College at Geneseo; she wanted to investigate this issue after she had experienced it herself.

Biological Family Building Options For LGBTQ+ Couples

One partner has donor sperm inserted into their uterus with a syringe to fertilize their egg. This can be done as part of an in-office procedure, with a doctor, or performed at home with a self-insemination kit. The partner who is inseminated also carries the pregnancy to term.

One partner provides their sperm, which is used to fertilize a donor egg in vitro. The embryo is then transplanted into a gestational surrogate’s uterus and they will carry the pregnancy to term.

One partner donates their eggs, which are fertilized in vitro (outside the body), then transplanted into the uterus of their partner, who will carry the pregnancy to term.

“For queer women, a fertility clinic is often a first stop for questions about insemination, but it can result in aggressive timelines and invasive treatments,” she says. Roth was recommended fertility testing and hormonal drugs to boost her chances of conceiving with donor sperm. Wary of the side effects of the drugs, she declined the treatment, deciding instead to try insemination at home without the use of hormones. She got pregnant with twins in her first month of trying.

While there are no quantitative studies on queer fertility to base guidelines on (most research on conception rates neglects to include people’s sexual orientation), there can be valid reasons doctors recommend fertility treatments earlier for queer women. The thing is, donor sperm isn’t cheap—$800 to $900 a pop—so some fertility pros point out that it’s in a queer woman’s best interest to make sure off the bat she isn’t dealing with any fertility roadblocks that might make pregnancy difficult, says Cynthia Murdock, MD, physician and fertility specialist in reproductive medicine at Reproductive Medicine Associates of Connecticut.

When advising queer women, Dr. Murdock, who is also a reproductive endocrinologist at Gay Parents To Be family planning, always suggests initial fertility testing (which can run $550 to $1,300) as well as an ovulation-stimulating injection and in-office insemination (that procedure alone can cost $300 to $1,000 on average), though none of that is technically necessary to try to get pregnant. “Patients can also track their ovulation and inseminate themselves at home with the aforementioned pricy donor sperm free of charge,” she notes.

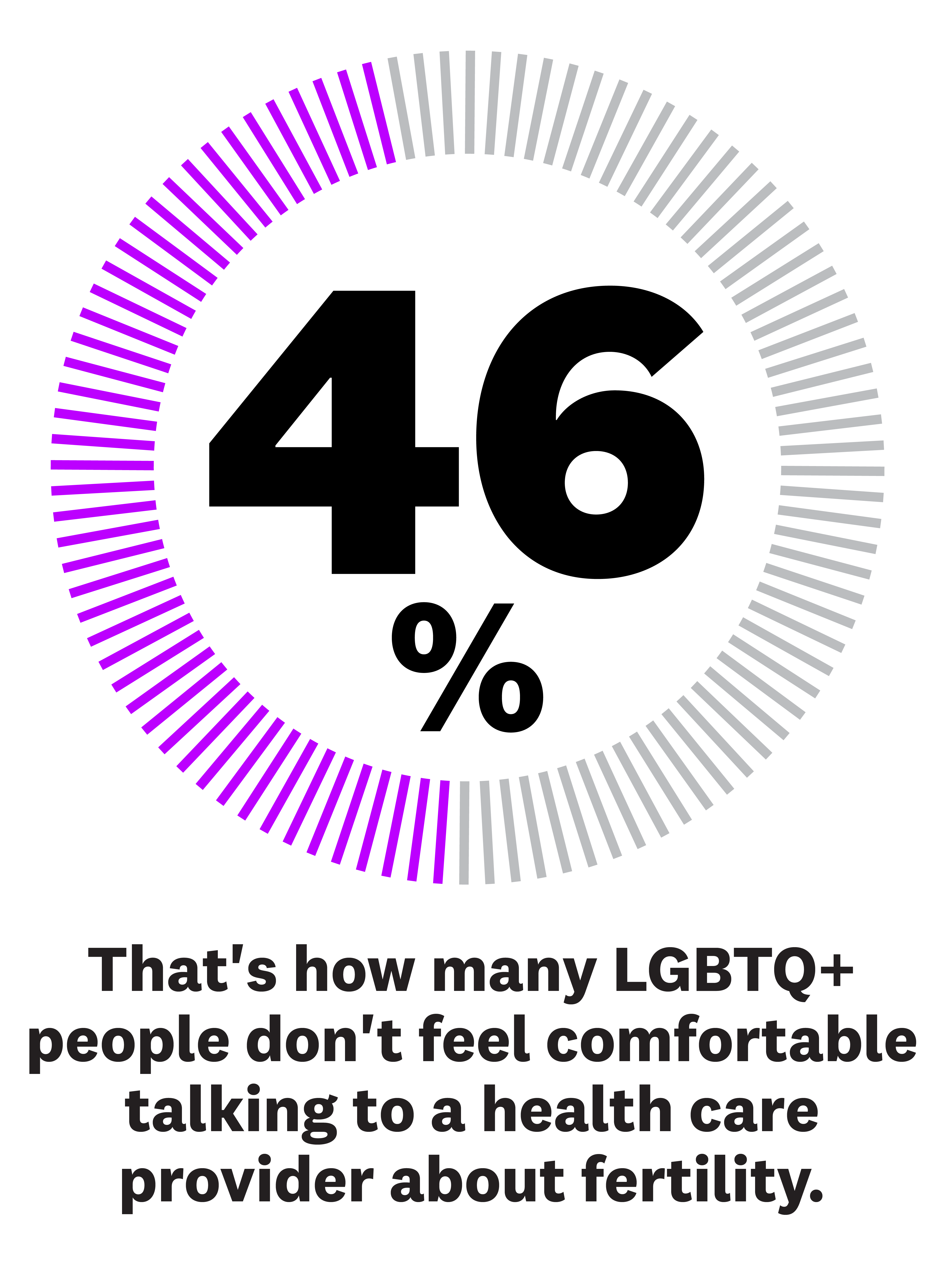

But this ambiguity around the best way to offer fertility care to queer women—and the added costs that can come with it—aren’t the only issue they face inside clinics, says Roth. “Even in seemingly queer-friendly parts of the country, outright or subtle discrimination in these spaces is an issue,” she says. Heteronormative intake forms, misgendering, lack of knowledge about LGBTQ needs and identity erasure from health care providers throughout the process is common, according to research from the journal Women’s Health Issues. That may be why 46 percent of LBGTQ people don’t feel comfortable talking to a health care provider about their fertility, per a survey from Modern Fertility.

On top of that, queer women often have to jump through hoops with their insurance providers to get any kind of fertility care covered, since queer needs aren’t explicitly outlined in many plans. This all adds up to a pregnancy experience full of needless financial and emotional setbacks.

Take it from these four women: Whether they’ve had children or are still on the path to parenthood, they want the world to know what it’s like to try to have a baby as part of the queer community. While their stories are different, they share a common hope: that in the future, medical resource providers, fertility practitioners, and researchers studying fertility do better by them by choosing to be inclusive of their experiences and needs.

“We’ve really struggled with: Do we want to do things ‘the right way’ in a clinic, which is massively expensive, or do as much as we can at home for less?”

I knew from a very early age that I wanted to be a mom. I always had a baby doll with me when I was little; my family even called me “the baby whisperer.” Now I’m married to the most amazing woman, and though we’ve been ready to start a family for a while, the process has taken a lot longer than we anticipated. We hoped to be pregnant last year—we planned on doing insemination and me carrying—but it hasn’t happened because of all the constant roadblocks we’ve faced.

First, I discovered that getting proper (or any) insurance coverage for fertility care is a nightmare when you’re queer. My insurance ended up offering some fertility care coverage, but I had to be medically infertile to qualify. The insurance company’s definition of medically infertile? Having had consensual unprotected sex for 12 months with someone of the opposite sex, without pregnancy. There’s zero acknowledgment of queer people and their needs within that framework. When we realized we wouldn’t be able to get coverage from our employee benefits, we tried to purchase our own fertility coverage. Dead end again. Fertility insurance is not available to individuals, only employers.

“It felt like everywhere we turned, someone was asking us to spend more time and money on testing and medication before we could even try to get pregnant.”

After hours on the phone with insurance companies and fertility clinics, my wife and I decided to visit a clinic and just pay cash for an initial consultation and to have some questions answered. Our home state is rather conservative, so we went out of state to visit what seemed to be a gay-friendly fertility clinic. The clinic was great, but we left with a laundry list of recommended tests, blood work, and procedures to complete before they would even consider doing insemination, which was going to blow our savings before even trying to conceive.

It felt like everywhere we turned, someone was asking us to spend more time and money on testing and medication before we could even try to get pregnant, adding months to our desired due date. I was so frustrated that I started asking other queer people about at-home testing that mimicked the checklist the fertility clinic had given us, but for a much lower cost (i.e., at-home genetic testing and insemination kits).

Throughout this whole process, we’ve really struggled with this question: Do we want to do things “the right way” in a clinic, with the guidance of a doctor, and all the recommended testing and medications—or do what makes the most sense for our family financially and emotionally, which is doing as much as possible at home and using a known sperm donor to save money? We’re torn between working with the clinic and paying for their help and just trying this at home, because time and money are not on our side. It’s something I don’t think people who need help trying to conceive should have to decide between.

At this time, we’ve completed STD, fertility, and genetic tests at home and have passed physical exams. We are going to use a known donor to leave us with enough money to try insemination at our fertility clinic. The lack of diversity and options at the sperm banks ultimately led us down this route. Since we are not spending $800 per vial of sperm, we can use that $800 to cover most of the insemination procedures, which are $875 per try. Once our legal paperwork with our sperm donor is drafted up and signed, we’ll be ready to start inseminations in July, assuming our clinic accepts all of our at-home tests and doesn’t require that we do even more work. Our fingers are crossed.

—Courtney Yazzie, 29, Utah

“Having to wait six months to get access to your sperm has very real consequences, especially when you’re already up against a biological clock.”

My wife and I met when I was 34, got married when I was 37, and started trying for kids almost immediately. We planned on me conceiving and carrying first, since I was older than her. I didn’t feel comfortable using a sperm bank. I want my child to be able to know their biological parent if they choose. There’s also not a ton of diversity in donors, and we wanted someone who shared my wife’s heritage (Chinese). So we asked her cousin to be our sperm donor.

We’re on the east coast and he’s on the other side of the country, so there were some logistical hurdles. I flew out to him a few times to try to get pregnant. Basically, he would go into one room and fill a cup with semen. I would take it and go into another room and use a medicine syringe to do self-insemination. I’d lie on my back for a bit, and that was it. Unfortunately, those inseminations didn’t end up getting me pregnant.

“Why should I have to prove I’m in a relationship with someone to have a bank store his sperm for me and give me access to it?”

At the same time, we were trying to have his sperm frozen and stored at a local bank so that I could try any time without flying to see him, and so that we could potentially use it for siblings. That’s where we ran into major problems.

When someone donates sperm, the FDA requires a six-month quarantine of it, so the bank can run STI tests and ensure it’s safe. My wife’s cousin was technically donating his sperm for us but we had already talked to him about testing, felt comfortable with his status, and I’d already had his sperm inside me multiple times. So per the FDA, he was a “directed donor,” not an anonymous donor, and didn’t need the six-month quarantine.

But at some fertility clinics we tried to work with, they refused to let us waive the quarantine. Some sperm banks asked that we pay thousands of dollars for STI and genetic testing in order to freeze it, even when I explained our situation and clarified that our donor had already done those things. We were able to get his sperm frozen without additional testing by having him say it was for his personal use (for example, with his own partner), and he gave the bank permission for us to order it. But when we wanted to transfer it to our name, we were told it was going to cost hundreds of dollars just to change the name on the account.

This is not how straight couples who want to freeze sperm are treated. Why should I have to prove I’m in a relationship with someone to have a bank store his sperm and give me access to it?

These delays have very real consequences, especially when you’re already up against a biological clock. I’m 39 now, and though I had no reason to think I’d have trouble getting pregnant when we started, I wasn’t able to after eight cycles of trying with our donor’s sperm. We couldn’t wait any longer, so now we’re doing reciprocal IVF using my wife’s eggs. That means her eggs have been fertilized—with a different known donor’s sperm—and I’ll carry our baby. We did our egg retrieval right before everything shut down because of the pandemic, and we’re now doing embryo transfers in hopes of a successful pregnancy.

—Elizabeth Barry*, 39, New York

“Our two pregnancies were emotional roller coasters that took us from all-time highs to all-time lows.”

My wife and I both wanted to play a biological role in our children’s creation, so we decided to use reciprocal IVF to conceive. That meant she would carry my egg so we could both be a part of the process.

Our first round of IVF was exhilarating. We were so excited during the entire process. The day we received all our shots in the mail was like Christmas morning. We couldn’t wait to get started. I mapped out who would be getting what shot on what day and if we were supposed to do it in the morning or evening. In the beginning, it was mostly me who had to get all the shots, since they prepared my body for egg retrieval. Meanwhile, we started looking for a sperm donor online. We tried to find someone who resembled my wife, Katie, as much as possible, and who also had similar interests to her.

As excited as we’d been about the IVF process, it didn’t pan out the way we imagined it at all. Our first round of egg retrieval failed—none of the eggs survived. We tried again, and we were lucky enough to have two embryos transferred to Katie. But in the first trimester, she miscarried one of the embryos. The experience was terrifying. Though one of the embryos survived, we spent the whole pregnancy worried we’d lose it. We didn’t have the option of just trying again endlessly since we only had a few IVF embryos left. We worried about every little thing. We didn’t want to buy anything for the baby because we weren’t sure we would have one.

“We were emotionally, financially, and physically drained trying to start our family.”

But as Katie’s pregnancy progressed, we started to feel little moments of joy. I remember feeling our baby kick for the first time. I wanted to cry. I couldn’t believe a little baby was inside there—a baby we both created with the help of science. It was an amazing feeling.

When our daughter Kennedy was born, I just couldn’t believe she was ours and she was actually here. I was overwhelmed with relief. I was no longer thinking about the pain from fertility procedures and needles, the mental pain I felt when our first round of IVF failed, or all the money we had spent on the process. We had our family now and our dream had become a reality.

After two years, we were ready to try for a second child. We were using a frozen embryo from the same batch as Kennedy, which seemed to be an easier process than going through egg retrieval and fertilizing eggs again.

After transfer day, Katie and I waited anxiously for the results. The phone rang and our nurse delivered great news: We were pregnant! But when Katie went in for another test, the hormones that signal a successful implantation were low, which our doctor told us meant she would most likely miscarry or have an ectopic pregnancy. We were told to watch Katie’s body carefully because if it was ectopic and untreated, it could result in damage to her reproductive system. We were terrified and heartbroken all over again.

Waiting for a miscarriage was terrible. We spent each day wondering when it would happen. We had a hard time talking about it because it just made us cry. Katie called me one morning and said she was bleeding, and we scheduled an ultrasound to see what was happening. It seemed impossible, but the ultrasound showed that our baby was still in there, still alive. Our doctor told us that we should still be cautious but that the baby was the size it should be. “This one was a fighter,” he said. Indeed, she was. Charlotte was born a year ago, and we’re lucky to have two healthy little girls.

Our last two pregnancies were emotional roller coasters that took us from all-time highs to all-time lows. We were emotionally, financially, and physically drained trying to start our family. Even though it cost us tens of thousands of dollars to make Kennedy and Charlotte, we’re starting the process of having a third baby. We know we need to be more cautious throughout the whole thing and not let ourselves get caught up in the excitement of receiving pregnancy news when that time comes. So much can change so quickly. But having our two girls has made every moment of the crazy, stressful process so, so worth it.

—Christina Bailey, 30, California

“On almost every visit to the fertility clinic, I had to come out again.”

After my wife had our first child, I was tagged in to carry our second. We went to a fertility specialist for help monitoring the timing of my cycles and to have in-office inseminations with donor sperm. The questions I was asked throughout the process, like, “So you are able to ovulate on your own?” and, “What ovulation-stimulating medications are you on?” made it feel like I had already failed at something. My labs were all normal, I was in my mid-30s. I wasn’t infertile…I was just a queer woman navigating a system that was not designed with me in mind.

This was further evidenced when half of the time it was assumed that I was straight, and the other half it was assumed that I had only ever been partnered with women. Had anyone asked me or looked at my history, they would have found out I am bisexual. The diagnosis I needed in order to receive insurance coverage was “male infertility.” Having the lack of a cis-male partner become my medical diagnosis only punctuated my feelings of otherness.

It was disappointing that on almost every visit, I had to come out again. I was told things like, “Don’t have sex for the next 48 hours since it can reduce sperm count,” or, “You can try on your own on other fertile days.” Providers often asked me who my wife was (or it was assumed she was a friend), and gave me pregnancy tests just to make sure I wasn’t already pregnant, multiple times.

I tried to make light of these harmful assumptions with little jokes like, “I’m married to a woman, so me being pregnant is pretty impossible, or at least…hard to explain,” and, “My wife and I keep trying but it’s just not happening for us!” They weren’t well received. It’s emotionally draining during an already stressful experience to have to constantly explain yourself and clarify your identity.

After 11 cycles of insemination, I got pregnant via IVF and gave birth to our second child. But there was so much that could have made the process better. My relationship and identity should have been recognized and acknowledged at the clinic, especially one in San Francisco that’s frequented by queer people. I don’t want to be told I should or shouldn’t be on medications or undergoing procedures based on timelines from studies of straight couples who were already dealing with infertility. I could have been spared a lot of time, money, discomfort, and tears with queer-informed care. There are plenty of LGBTQ+ people who are trying to use assisted reproduction to conceive. Data and recommendations based on our experiences need to exist so we can get proper care.

—Allegra Hirschman, 39, California

*Name has been changed

This article is part of Women’s Health 2020 Pride Month Coverage. Click here for more.

This article is part of Women’s Health 2020 Pride Month Coverage. Click here for more.

Source: Read Full Article