Moby Opens Up About His Suicide Attempt and Living With a Panic Disorder

In October of 2008, Richard Melville, known to old friends and raving fans and sour critics simply as “Moby,” the transformative and controversial artist who ushered electronic dance music into the mainstream and played across the world, put a plastic bag over his head, fastened it with a belt, and closed his eyes. He’d been thinking about death for years, waking up every day disappointed that he hadn’t died in his sleep. He envied and resented Heath Ledger, someone who had, that year, died in his sleep. But that morning, after wandering through his Mott Street apartment in New York, crying and repeating to himself, “I just want do die,” Moby decided to do it. “In a weird way, it just seemed like the most practical course of action,” Moby says. “I was lonely and sad and sick and drunk and high, and I’d been that way for quite a while. And nothing was getting better.”

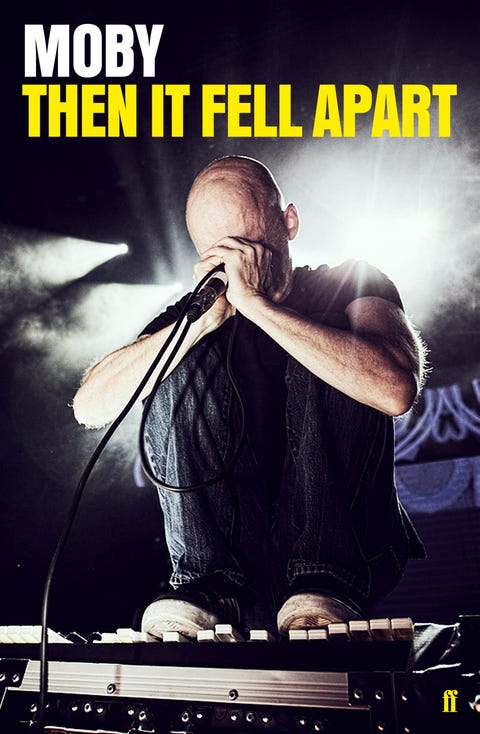

Faber & Faber

Now, ten years sober, Moby says it’s important he share this “dark side.” His new memoir, Then It Fell Apart, comes out this week, a chronicle of his ascent into fame and descent into addiction and debauchery. He hopes that writing these moments helps make sharing easier, both for himself and for his audience.

Moby once thought of suicide as a similar communicative act. “You’re advertising the extent to which you were in pain,” he tells me.

If so, then Moby’s discography plays like one long, beautiful, painful advert, though, one often disguised by fast, upbeat dance tempos. The book’s title Then It Fell Apart are the lyrics from one such record, 2002’s “Extreme Ways.” “Extreme” encapsulated much of Moby’s drug-fueled life of late-90’s and early 00’s fame. It was a decade in which he never slept before sunrise, a nonstop sundown pursuit through bars and nightclubs toward “oblivion,” a state where he’d drink or snort enough to, hopefully, never wake up ever again. In the song, “extreme ways” are “back again,” which, if it wasn’t so melodious, might play like a more evident admission of relapse. Moby’s third verse, a portent for an October morning six years later: “I closed my eyes and closed myself / And closed my world and never opened / Up to anything.”

Moby’s father died when Moby was two, after driving drunk into a bridge in New Jersey at 100 mph. Then It Fell Apart reckons both with the fallout from this death as well as it’s ultimate cause: alcohol. Moby calls alcohol the molecule, something he was both physiologically predetermined to enjoy—and found at the age of ten—and something he was psychologically motivated to abuse. “It suddenly enabled me to feel calm and unafraid for the first time in my life,” he says.

Moby got his start in Manhattan, playing hip-hop and dance to a crowd of mostly gay, black, and Latino ravers. That was the New York City Moby loved: hot, sweaty clubs with dancing and energy and fun. In 1991, he released “Go,” a dance anthem that sampled the opening to David Lynch’s Twin Peaks, and soon he was touring and riding a small current of fame across Europe. Fame was joyous. Fame was playing on a barge in Belgium in front of hundreds of ravers. It was having sex in a hotel shower for the first time. Fame was also possible alongside sobriety, and for the first half of the 90s, Moby never touched a drink.

But then it was New Year’s Day in 1995. Moby was at a bar with friends. His fame, he felt, was waning. He had suffered from a panic disorder since he was a kid, and so even though he often felt lonely, he feared intimacy. After he called an ex-girlfriend and a man answered the phone, Moby hung up, went to the bar, and immediately ordered a beer. And then another. And then another.

By 1999, Moby was drunk or high almost every night. He would release another album that year, Play, probably his last, he thought.

Play was a collage, part 80s-techno, part jazz, part blues, part folk, part 50’s gospel and a cappella, and part spoken word. Songs inspired by bible verses, by classical music, by walking around Chinatown at 5am, and, ultimately, by New York City. And by drugs. Indeed, it was an album that began with a rave energy, faded into a chemical haze, and then ended with a soft choir. It was a dirty, exciting 90’s New York City trip.

And it rocketed Moby into fame.

Not small-European-tour fame, but big-pop-star fame. Now fame was a fifty-foot billboard of himself on New York’s Houston Street. Fame was Natalie Portman and Madonna dancing next to his stage, Russell Crowe grabbing and yelling at him in an Australian bathroom, and gold and platinum records stacked in the hallway of his small Mott Street apartment. Fame was also lots of spontaneous sex, ecstasy, and vodka. And then, when the fame began to wane, again, fame became cocaine, meth, and any drug offered.

“Fame was gold and platinum records stacked in the hallway of his small Mott Street apartment. Fame was also lots of spontaneous sex, ecstasy, and vodka.”

“I fully believed that I knew exactly what I was doing,” Moby tells me. He thought that if only fame and success worked out, then things would be perfect. But they weren’t.

Ultimately, Moby did wake up in October 2008. The plastic bag lay on the floor. He had torn if off, unconsciously, sometime during the night, or rather, the day. A week later, Moby headed to the only AA meeting location he knew in the city. He had avoided sobriety for years, but this week felt different.

“There’s a cliche in AA: the first half of the first step is the only part you actually need to do really well,” Moby says. Moby’s not averse to the AA cliches. In fact, he found the procedure revelational. “[I was asked] How often do you drink in moderation? And my answer was ‘never.’ And how often do you leave a drink unfinished? And my answer was ‘never.’ How often do you drink considerably more than you planned on drinking? And my answer was ‘every single time I go out drinking.’” He describes the revelation as finally and fully accepting “the evidence”—a broken body, broken friendships, a broken plastic bag. “That true admission—when you’re able to finally admit to yourself that you are an alcoholic—it creates a seismic, almost tectonic shift.”

“Then It Fell Apart” ends in 2008 with Moby’s “true admission.” But for Moby, that year was when a different, redemptive story began.

Sobriety wasn’t just separating myself from the molecule, he says; it meant also interrogating the underlying emotional dysfunctions that made alcohol and drugs so powerful in the first place. He had done dynamic psychoanalysis in the early 2000s, which helped him identify particular childhood trauma as cause for much of his panic and alcoholic escape.

Moby later turned to cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT) and a regimen that included exposure techniques. “I remember early on in CBT, this image came to me of looking into a hallway and seeing a shadow of some huge, terrifying 10-foot-tall monster,” he says. Moving toward the shadow would be the image for much of Moby’s therapy: forcing himself to commit to romantic relationships, get close to people, confront the panic.

“You’re not just giving up drinking. You’re giving up the belief that you know what you’re doing.”

When Moby speaks about this confrontation, he talks a lot about acceptance. He says we all believe that if we make the right choices, we can protect ourselves from the “unavoidable facts” of the human condition, namely, “confusion and death.” We engage in material exchange to alter these facts. We seek fame to live longer. We drink and sleep around to feel connected, less confused. Clarity comes only with acceptance of these facts and the revelation that you cannot alter them. Moby knows it sounds like wishy-washy-wannabe-Buddhist-new-age bullshit, but he doesn’t care. Acceptance and giving-oneself-over-to-the-universe have become important personal mantras. “You’re not just giving up drinking,” he clarifies. “You’re giving up the belief that you know what you’re doing.” You’re embracing the unavoidable fact of confusion, rather than initiating the fact of death.

And he wouldn’t change anything. Not that things happen for a reason. But that one learns only from failure. “Even the worst, most degrading, stupidest, most self-destructive things I’ve done, I wouldn’t change,” he says. As a god hovering over his past self, Moby would allow that self to drink and tie a plastic bag around his head, because he knows only after all these moments, only after failure, would that self admit he needs help.

Because the alternative might mean something that flirts too closely with the final track of Play’s NYC trip, “My Weakness,” either an ascent to some sunrise Nirvana or an empty drug-induced death. The song’s only lyrics, on repeat: “Ooh/ Weakly mind, weakly, / Ooh I go home.”

Source: Read Full Article