Imaging tumor stiffness could help enhance treatment for breast and pancreatic cancer

Using a non-invasive imaging technique that measures the stiffness of tissues gives crucial new information about cancer architecture and could aid the delivery of treatment to the most challenging tumours, new research shows.

Magnetic resonance elastography was able to visualise and measure how stiff and dense tumours are in mice. The technique, which can be implemented on conventional clinical MRI scanners, may help select the best treatment course for some cancer patients.

Scientists at The Institute of Cancer Research, London, found that using their new type of scan could assess the contribution of collagen to relative stiffness across a number of different tumour types.

This in turn could identify tumours in which there is the potential to use new drugs designed to ‘weaken’ the structure holding together tumours—thereby giving other drugs access to cancer cells in the centre of the tumour.

Initial studies established that collagen was key to keeping breast and pancreatic cancers stiff and inaccessible to treatments. In contrast, tumours arising from the nervous system, such as some forms of childhood cancer and brain tumours, were relatively soft and lacking in collagen.

The study, published in the journal Cancer Research today, was largely funded by the European Union, Cancer Research UK and the Rosetrees Trust.

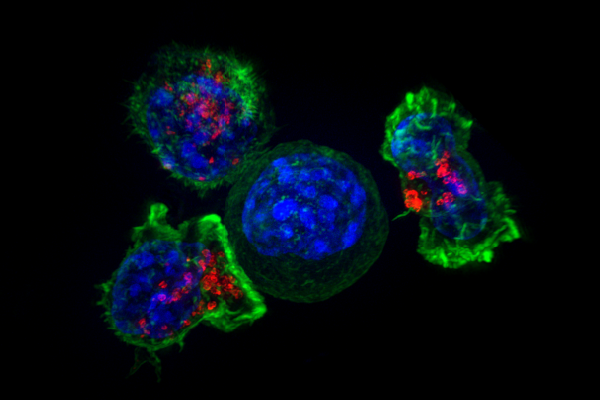

Tumours are masses of uncontrolled cellular growth, formed of dense and compact networks of cells, structural fibres and blood vessels. It can therefore be challenging to effectively deliver treatment to some tumours as the mass is often stiff and difficult to penetrate.

The researchers at The Institute of Cancer Research (ICR), working in collaboration with King’s College London, found that, for example, breast tumours were around twice as stiff as brain tumours and around three times as dense. The major contributor to this increased tumour stiffness was collagen—a key component of bone, cartilage, tendons and the extracellular matrix that holds tissues together.

The findings suggest that the scan can monitor the weakening of the tumour structure through drugs designed to break down this extracellular matrix, such as collagenase. The technique could also be key to identifying the optimum time to efficiently deliver chemotherapeutic agents by showing when the tumour is most vulnerable.

Accordingly, the researchers found that the administration of collagenase resulted in a clear overall reduction in the elasticity and viscosity of breast tumours in mice—both of which fell by around a fifth.

The ICR researchers found that MR elastography provided extra details about tumour structure and density in addition to the information about growth and size given by standard MRI scans.

Study co-leader Dr. Simon Robinson, Team Leader in Magnetic Resonance at The Institute of Cancer Research, London, said: “Our research shows that this new type of scan can give valuable diagnostic information about breast and pancreatic tumours non-invasively by assessing their stiffness. If confirmed in a clinical trial, we could use this technique to identify patients most likely to benefit from treatments that target the dense scaffold upon which these tumours grow. It gives us a new way of looking at cancers, and a potential way to monitor new treatments that alleviate tumour stiffness in order to help enhance the efficient delivery and uptake of chemotherapy.”

Study co-leader Dr. Yann Jamin, Children with Cancer UK Research Fellow and Senior Researcher in the Magnetic Resonance team, at The Institute of Cancer Research, London, said: “There’s a lot of research activity centred on finding new therapies designed to help anti-cancer drugs reach their target in breast and pancreatic cancers, which can be so stiff and dense that they are impenetrable.

“We are very excited to have found a rapid scan that can be incorporated into a current routine clinical MRI examination and can potentially monitor the effects of these new tumour-weakening therapies, and assist the development and delivery of medicines which could save or extend lives.”

Natasha Paton at Cancer Research UK said: “Some tumours, like breast and pancreatic, are stiff and dense. Because of this, drugs are unable to reach deep inside the tumour and the cancer becomes harder to treat. Results of this pre-clinical study in mice show that using elastography to measure stiffness alongside standard imaging scans may help doctors deliver treatments more effectively to cancers that are known for their stiffness.

Source: Read Full Article